About two weeks ago, Kay Warren's anger boiled over. The co-founder of Saddleback church wrote on Facebook, "As the one-year anniversary of Matthew's death approaches, I have been shocked by some subtle and not-so-subtle comments indicating that perhaps I should be ready to 'move on...' I have to tell you – the old Rick and Kay are gone. They're never coming back. We will never be the same again."

Within seven days, her 800-word missive had gone viral with 3.75 million readers and 10,000 comments. Thousands of individuals shared stories of lost family members due to illness, suicide, or accidents. They recounted the insensitivity of family and friends, and their own shame and guilt about their overwhelming grief.

Mental illness and depression are linked to suicide, and Matthew had borderline personality disorder. Today [March 28], Saddleback senior pastor Rick Warren and Kay will convene one of the largest ever, one-day gatherings of Christian leaders focused on the role of churches in addressing mental illness. The event is sold out. Recently, Kay Warren agreed to her first in- depth interview about her son's suicide with Timothy C. Morgan, CT senior editor, global journalism.

The response to your Facebook post has been staggering. Was it written on the fly or what?

In the last month, there were four instances where I was subtly or not subtly moved along. I was having lunch with a mother younger than I am who was recently bereaved. Her loss was 14 months ago. I said, "Before the one-year mark was up, did you have people telling you, hinting or saying to you that you should move on?" I asked other people who had lost children. I was hearing the same story. It just made me mad. I jotted off that Facebook post and have been completely astounded by the response—3,780,000 views and more than 10,000 comments.

Aren't most of the comments supportive?

Somebody wrote, "I want to print words around my neck that say, 'Please just read Kay Warren's Facebook post.'"

I want to honor those people who told me their story. I identify with them. I grieve with them. I weep with them. People feel guilty and ashamed. They feel guilty that their loss tanked them so badly and shame that it still has them in that place of deep grief. Rick and I have been the beneficiaries of an extraordinary outpouring of love and sympathy and empathy and compassion.

What do people who have lost children to suicide hope for?

I'm saying, "Don't push me to move on faster than I can go." In many ways you're forever changed. Jerry Sittser says in Grace Disguised, "It's really pointless to compare grief." When my father passed away six years ago at 86 with cancer, I grieved and I mourned and I wept, and it still touches my heart. On the other hand, my dad at 86 had lived a very full and rich life and had seen the fulfillment of his dreams and had a rich marriage.

I can tell you the experience of losing my 27-year-old, mentally ill son a year ago was not at all the same as losing my dad. He died young. He took his life, and he did it in a violent way. We are scarred. We have two decades of living with a severely mentally ill person that traumatized us. It's not clean grief. There's guilt. There's regret. There's horror.

The grief of my friend, whose daughter was murdered, has an aspect that's even different than mine. I haven't walked in her shoes. We're so quick to say, "Oh, I know how you feel," and we usually add the words exactly: "I know exactly how you feel." I want to say, "No. Excuse me. You do not." The best we can do is to say, "My heart breaks for you. I have experienced grief, and my heart aches for you."

And don't ever start a sentence with the words "at least." Any time I hear the words at least coming at me, I know it's going to be a sentence that makes me mad: "At least you had him for 27 years." "At least you have other children."

Looking back, how do you describe what you call "the old Rick and Kay"?

Because of our love, we conceived a child together. I birthed him from my body. He was a part of me. A part of me is no longer here. How can I be the same? For us as a couple, as a family, there were five of us; now there are four. Our child murdered himself in the most raw way I can tell you. Suicide is self-murder. Our son, the murderer, was himself. The trauma of knowing what he did to himself, how he destroyed the body of this child that we loved. He did it to end the pain. How could we ever be the same? Trauma changes you. I can't ever go back to who I was.

On CNN, you said, "I'm terrible but not okay. We're going to survive, and some day we'll thrive again." Is this still true?

I said at Matthew's memorial service, "We're devastated, but not destroyed." I don't know that you ever stop being devastated by catastrophic loss. In the last year-and-a-half of his life, we lived right on the edge every day. I would talk about it with close friends and say, "It's like sitting on the edge of hell."

I determined some time ago that I was not going to let anything destroy me. I had my years of saying to the Lord, "You were at work in Matthew's life yesterday, today, and you'll be at work in my life every day until I meet him again."

I heard an incredible sermon by Hillsong's Brian Houston last summer, called "Glorious Ruins." He talked about Lamentations, Ezekiel, Jeremiah, and all of what happened to Israel. Ezekiel, chapters 36 and 37, talks about how Israel was ruined. God says, "I will resettle your towns, and the ruins will be rebuilt. The desolate land will be cultivated instead of lying desolate in the sight of all who pass through it" (Ezek. 36:33-34 NIV).

This corresponded with a favorite quote by Eric Liddell, the Olympic runner. He said, "Circumstances may appear to wreck our lives and God's plans, but God is not helpless among the ruins." That phrase "God is not helpless among the ruins" has kept me where I can say, "yes, devastated but not destroyed." My life has been torn down to the foundation, ruined, and yet, at the same time, and God has a plan for us.

You've shared before about your hope box and the mystery pot. Are those still useful?

They sit right on my table right next to where I have my devotions every day. Every time I would read a Scripture that gave me hope I would write it out and put it inside that box.

Late on the night of April 4, I had a texting conversation with Matthew. I knew that he was threatening to kill himself. All of a sudden he quit texting. I was very frightened. Rick was sick with pneumonia, and I pulled him out of bed and we drove over the Matthew's house. I banged on the door, rang the doorbell. He didn't answer. He had threatened that if we called the police that he would take his life if they even got near. We found out later that he had actually taken his life.

I couldn't look at that box anymore. It mocked me. I took all the verses out and I threw them away. The box just sat empty. Even though Romans 5:4-5 says, "Hope doesn't disappoint," I was severely disappointed by hope.

My son shouldn't have taken his life. I kept screaming that night, "This is not how it was supposed to end!" What did I gain by believing so passionately? I could become a bitter atheist. I didn't know how to believe again. I asked God to start showing me verses that could rebuild my hope for what was next in our life.

Slowly I've been repopulating that box with verses. The first one God gave me was 1 Corinthians 15:43, and it says, "These bodies are buried in brokenness, but they will be raised in glory." When I stand or kneel or lay on Mattew's grave, I say every time "God, Matthew's body was buried in brokenness and in weakness, but you will raise him in glory and strength."

Hope is alive again in me. I'm left with questions. Why did I pray so passionately and believe with all of my heart that God was going to heal Mathew only to have him die? A friend heard me talking about that, and she bought me this little ceramic pot, and I've written those questions out and they're on little strips of paper, and they're all inside that little pot.

That's the essence of our faith. It's living with hope in the face of mystery. We live a life of faith completely full of hope, staring mystery right in the face. You can't have one without the other. Your faith won't survive without hope, and hope won't survive without the realization that there are mysteries that will not be answered. If you can embrace both, you can have a vibrant faith.

Why are we so bad at expressing grief?

Growing up in an evangelical church with my dad as a pastor, he didn't express his negative emotions. It was all just happy, happy, joy, joy. You just didn't talk about it. My brother was a heroin addict, and they didn't tell anybody in their church what they were going through. I didn't know anybody growing up that talked about their feelings.

As a child, I was molested and had not dealt with it. When Rick and I got married, I told him in this flat, emotionless voice, "It had nothing to do with me." It was in the past. Within days of getting married, our honeymoon was a shambles and we were broken people.

We started marriage counseling, and I began to see what a wrong model I had lived with. I remember coming home from a counseling sessions lying on our bed just staring up the ceiling, and I felt the love and acceptance of God for the first time in my life. My spirit soared.

I said to Rick, "When we pastor a church, even if I have to stand on the rooftop of that church, I will tell people that we are just like everybody else. We are sinners. We are broken. There are some days I'm not sure God exists. Sometimes I feel like this is a big cosmic joke. We need God to get through every single day." So we made a determination to do that.

What other resources have been helpful?

Ann Weems has a book called Psalms of Lament. She's written these psalms of lament that articulate in one of the most powerful ways that I've seen what it's like to lose someone and to just want to cry out and scream and moan and sometimes accuse God, if you will, of not loving us or not loving our loved one or abandoning us. Yet she comes back to that place of trust.

Another one is Steven Curtis Chapman's CD Beauty Will Rise (2009).

You have an anniversary coming up—April 5. Do you have something clear in mind that you're going to do?

I want to be with people that I love. I will go to the cemetery. The cemetery comforts me. For me, it helps me accept the reality, because a part of me waits for him to walk in the door. The cemetery actually is a reality check for me. I connect back with God into that place of hope. This isn't the end of his story. There is more to this story.

People were very moved by Rick's comments, "In God's garden of grace even a broken tree bears fruit." How does that influence your thinking?

Two levels: First it relates to the kind of person that Matthew was. He was this funny, quirky, hilariously silly guy. He made me laugh. He is always so exquisitely, sometimes painfully, sensitive to people and things around him.

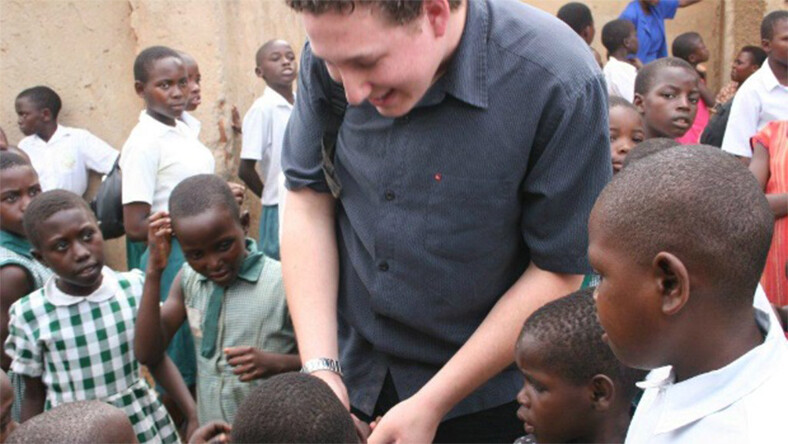

We put on his headstone "Compassionate Warrior." He fought for others, even though he himself was very broken and knew his brokenness. As he traveled with me around the world, he was brokenhearted by what he saw. But he was so sensitive and broken, it turned in the other direction. It made him bitter. He was a broken tree, but he still produced beautiful fruit.

There are people who have told me that Matthew saved their lives after his death. They said, "I don't want to do that to my family." Others say, "I've taken suicide off the table because I don't want that to happen to my family." A young guy told me, "I heard of Matthew's story after he passed away. I've been suicidal for such a long time, but it drew me to your church. Here I've learned how much God loves me, and so Matthew saved my life." The tree continues to bear fruit.

How has Matthew's life changed your view of the mental health system?

The mental health system is just broken in the United States. I can't say that strongly enough. Not that people aren't trying and not that there aren't some really wonderful, compassionate people in the field of mental health. But it is so complicated. And most of the attempts to help don't always help.

In the conference that we're doing is a little pebble in the giant lake of mental illness. But the church has a role to play. Christ followers have to be in those conversations, and we have not. And we must.

When you realize that a large portion of people go to either their priest or their pastor or their rabbi first before they even go to a healthcare professional, it makes equipping faith leaders more urgent than ever. Most are not well equipped. Pastors are dealing with people with mental health issues every day.

Are you thinking through the life and sacrifice of Christ in a different way?

That's a hard one. I've encountered each person of the Trinity in this last year in ways that I don't recall before. It's all about God. He is sovereign. He could have saved my son. He could have healed him. He could have prevented him from taking his life. At the end of the day, it is all at God's doorstep.

When Matthew couldn't face another day here and he ended his life, he fell into the arms of Jesus. The words of an old hymn "Out of my bondage, sorrow and night, Jesus, I come." I envision Matthew saying those words in the moment that his spirit left his body and Jesus picked him up. I can just envision Matthew saying, "Jesus, I come into Thy freedom, gladness and light. Jesus, I come." (Sleeper, 1887) My encounter with Jesus is that of the Savior who receives and embraces.

The Holy Spirit? I've encountered his comfort and the truth that he has sealed us. Matthew's faith in Jesus Christ is as a child he was sealed, and nothing could take him. Nothing could take that salvation from him.

I've encountered the Trinity—in ways that have kept me going.